Each Tuesday for the month of February I’m posting a different story about my character Marla Mason. This week we have “A Cloak of Many Worlds,” written as a Kickstarter reward for one of my previous crowdfunded projects. This one’s a bit unusual, in that Marla doesn’t actually appear in the story, apart from a couple of mentions — but it’s about an old friend of hers dealing with a dangerous entity that used to belong to her.

(This is a transparent attempt to tempt people into supporting my Kickstarter for the new Marla novel Bride of Death.)

A CLOAK OF MANY WORLDS

Bradley Bowman — known, in most realities, as “B” to his friends — was getting pretty good at being a god. He hadn’t gotten much in the way of training, as his predecessor had died (or, more accurately, committed suicide), but since one of the perks of the position was a vastly enhanced mental capacity and total mastery of time, space, and the multiverse, he’d figured out things pretty well just by muddling along.

He was more than a god, really. Gods feared him — at least, those that believed in him did.

B sat at a small wrought-iron table in a gazebo in an imaginary garden, buttering a real piece of toast. When he took a sounding, he found an amazing 89% of himself was at least content, and 67% would have gone so far as to call it “happy.” A good morning, then. One of the best.

His lover, Henry, sat across from him, reading a French-language newspaper from a world where Napoleon’s empire had spanned the entire globe and persisted for two centuries. Henry had died of a drug overdose in most of the universes B had visited — back in timelines when B was still mortal, and so capable of uncomplicated linear heartbreak. B had taken advantage of his position to scoop one particular instance of his lover from a doomed timeline and taken him here, to the house outside space-time, to live as B’s immortal companion.

He was pretty sure such things were against the rules, except, as far as he could tell, there were very few rules, and no one to enforce them anyway. As long as he didn’t damage the structure of reality itself (an act which would be instantly self-negating, like a fire choosing to extinguish itself) he could do what he liked. There were other Powers his equal or better — he’d met them, he was sure, when he “interviewed” for this job — but thinking about them was like trying to look at the back of his own head.

Once he’d tried to save a few versions of himself who’d died unpleasantly in the past, but without success; he could see them, but trying to touch them was like squeezing smoke. There weren’t many rules… but there were, apparently, a few fundamental laws that couldn’t be worked around.

B’s job was to protect the integrity of the multiverse. To prevent creatures — apart from himself, and he didn’t count — from passing from one reality to another, shredding the fabric of space-time as they went. To guard against incursions from Outside, that mysterious space (or collection of spaces) where other entirely different universes bubbled in the quantum foam, and from In-Between, the dark shadows between the branches of parallel and proliferating realities, where dwelt terrible predators composed of equal parts biology and geometry.

His domain was not infinite, but it was very large, and ever-growing, as with each passing moment, in each universe, new choices were made right down at the quantum level, each choice spawning a new universe, endlessly branching, endlessly diverging. But B could be everywhere at once, if need be; so that was all right. And it wasn’t as if there were many real dangers. Cross-dimensional travel was rare, the dwellers In-Between mostly seemed happy to stay there eating any foolish sorcerers or science-explorers who breached their domains, and as for Outside, well —

“I dreamed about the cloak again,” Henry said, not looking up from the paper. He was blond, young, handsome, a lock of hair falling across his pale green eyes at almost all times, and his voice poured like honey when he said the least little thing.

B frowned. Contentment levels in the collective dropped precipitously. “Shit,” he said.

“Once is happenstance,” Henry said, rustling the paper. “Twice is coincidence. Three times — ”

“Yes, I know,” B said, and put down his toast.

#

B contained multitudes. He’d once been a mortal man, living a mortal life. He’d existed in tens of thousands of realities — but when he chose to accept this position, the wave-forms had collapsed, and he’d become a single individual, effortlessly containing the memories and experiences of all his counterparts. He thought of himself sometimes as “the collective,” since he was an amalgam of many, acting as one. He could spread out again, near-infinitely, sending versions of himself wherever they were needed in the expanse of time and space, every copy in continuous psychic contact with the main body, but after that breakfast most of him was together, standing on the frozen emptiness of a version of Earth that had drifted a bit farther from the sun than most, becoming a ball of nothing much but dirty ice, utterly lifeless.

There were a pair of cloaks wadded-up at his feet, made of white cloth, lined inside with an ugly bruise-purple, the color even more shocking than usual in this pale wasteland. “You little shits,” he said, kicking one of the cloaks. “How are you getting inside his head? I know you whisper and tempt and wiggle your little psychic fish hooks into people’s brains, but Henry isn’t even in this reality, he’s not in any reality, we’re curled up in a separate dimension. So how the fuck…”

Not for the first time, B considered picking up the cloaks and hurling them into a sun — or a black hole. The problem was, he couldn’t be sure what consequences that might have for the sun, or the singularity.

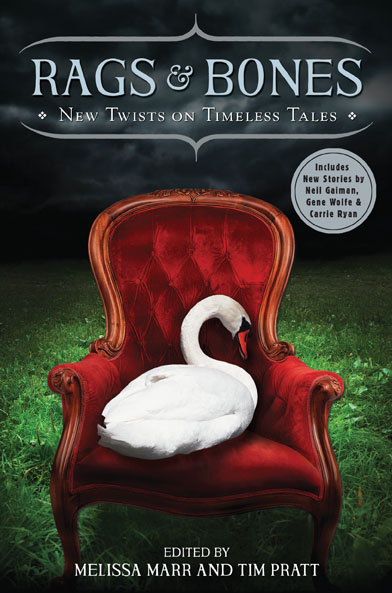

In many of the universes where B had been mortal, he’d made friends with a sorcerer named Marla Mason, who often possessed a magical purple-and-white cloak, an artifact of great power. In many of those universes, she discovered the cloak was a malign psychic entity bent on the utter domination of the world. Without a host body — a wearer, essentially — the cloak was largely inert, capable only of small telepathic whispers. Once it found a host to wear it, though, the cloak tried to possess the wearer’s body, and from there… onward to conquest, working magics that were unmatched in the multiverse.

On many of the worlds where Marla wore the cloak, she was unable to resist the cloak’s power, and became a genocidal tyrant. Bradley had stepped in on a micro level not long ago, as a favor to a version of Marla he was particularly fond of, and he’d taken a couple of instances of the cloak away, putting them here in this wasteland, where they could do no more harm.

The cloaks worried him, though, because they were from Outside — the only Outsiders he’d ever encountered. They didn’t belong to his multiverse, but came from some other entirely different universe. The physics (and metaphysics) of B’s multiverse didn’t apply to them — in some senses, this place was inimical to them, and the cloaks needed a physical host to support them just like an astronaut needed a space suit to function in the airless depths.

But in other ways, this multiverse was easy pickings for the cloaks; their magics were all but unstoppable here. And of course there were more of them every day, every moment, as the multiverse continued to branch, spawning new copies of the cloak with each variation. Sure, many of them were lost, or locked away, or sleeping and lying dormant without hosts, and they were all stuck in their respective realities, but still — they were wrong, and their existence troubled him.

Clearly, they had powers B didn’t begin to understand, and since he was supposed to understand everything in his multiverse, that was irksome. He needed to know where they’d come from, and what they wanted, and how they were whispering to his boyfriend… and how serious a threat they posed.

Fortunately, he was in a position to find out.

#

Henry followed him, but just to the top of the basement stairs. “Are you… you really have to go down there?”

B shrugged. “Some of them know things I need to find out.”

Henry blew a mouthful of smoke toward the ceiling — no reason to avoid cigarettes, here; they were beyond things like cancer — and nodded. “Okay. I just know how much they creep you out.”

“The basement’s not my favorite place,” B agreed. “But sooner started, sooner done.” He unhooked the padlock on the door — which was much more than an ordinary padlock, of course — and pulled it open. He descended solid stone stairs to a space so well-lit not a single shadow could collect in the corners. The walls were lined with man-sized glass containers, curved at the top like bell jars, each one holding a different version of B himself, their eyes closed, motionless but dreaming.

One Bradley was so disfigured he was barely recognizable, face a collage of scars, dressed in the shreds of a military uniform that was clearly from the Hugo Boss school of stylish fascism. Another was missing half his head, the damaged parts of brain and skull repaired with shiny metal plates and alien technology. A third had shockingly snow-white hair, and his left arm had been replaced by a long, blue-black tentacle that twitched and writhed even in the depths of suspension.

These were the versions of Bradley Bowman that had been purged from the collective. They were insane, or power-hungry, or otherwise dangerous, all from worlds that had suffered terrible agonies at the hands (or claws, or mandibles) of supernatural or extraterrestrial menaces — since B was a powerful psychic in nearly every reality, he was often dragged into the plots of such creatures, and sometimes terribly changed in the process.

The imprisoned version of himself that B needed to address today was fairly typical in his appearance, but reaching out to him mentally, B felt the void at the center of him, the profoundness of his broken places, the depth of his hunger. His neck was terribly scarred, as if he’d been scourged with a whip of needles; and in a way, he had. That version of B called himself the Host.

There were several realities in which B briefly wore the purple-and-white cloak, taking on the power and burden temporarily from his friend Marla Mason to help save the life of another. But this Bradley, the Host, for whatever reason, had lacked the willpower to resist the cloak’s whispering for even an afternoon. He had submitted to the cloak’s will, slaughtered Marla… and over the course of the next year, combining his own vast psychic gifts with the cloak’s brutal magics, he’d subjugated the entire Earth. He’d lost his empire when all the versions of B combined and ascended to meta-godhood, leaving his government in shambles (and the cloak itself abandoned, and in need of another host).

Most of the cloak’s hosts lost their minds when they were possessed, becoming vestigial things, but because of his psychic powers, the Host had managed to wall off part of his psyche, keeping it whole and intact. Unfortunately… he’d come to love the cloak. To love the power. The ability to do anything, without consequence or hesitation. His presence in the collective had been intolerable, like having a splinter in your eye, so B had sealed him away here… but now he needed the man’s insight.

B touched the glass jar. It shimmered out of existence, and the Host opened his sea-blue eyes.

A conceptual shift later, B sat in a steel chair in an interrogation room that lacked windows or doors. The Host sat across the scarred metal table from him, draped in chains. He smiled, showing teeth sharpened to points, then lashed out psychically, trying to seize control of the collective. It was a hopeless gesture — he was outnumbered literally billions to one — but B still reeled backwards under the ferocity of the assault.

“Well,” the Host said. “Worth a try. I didn’t become ruler of the world by never making an effort.”

“You weren’t the ruler of a world,” B said. “You were just the mount the ruler of a world rode.”

The Host shrugged. “The cloak and I had a more equal partnership than you’d like to admit. She burned the humanity out of me, to let me achieve my true potential, and she accepted my counsel.”

“Oh, I know that,” B said. “Which is why you’re here. I want to know about the cloak. What it is. Where it came from. What it’s doing here.”

The Host raised an eyebrow. “You’re something more than a god, brother. But you are wholly ignorant of the cloak’s true nature. Doesn’t that tell you something? Doesn’t that make you realize the cloak deserves to have dominion over this multiverse?”

“A case could be made,” B said. “Except for the bit where she wants to eradicate all other life.”

The Host shrugged. The scars on his neck where the cloak had clung, sinking the needles of its pseudopods deep into his flesh, were red, as if still infected. “You can’t blame her. Would you want to move into a house infested with roaches and centipedes, the bathtub full of slime eels, spiders in the pillows, slugs in the cupboards? That’s what we are to her — what all life is. She needs to keep a breeding pool of sentient creatures around, of course, to act as hosts, since our reality is unpleasant for her — it makes her very sleepy, like a lack of oxygen does for humans — but otherwise… things are much more beautiful without the slime mold of life everywhere. I came to see things her way.”

“I know all that. Tell me what I don’t know. Where does she — it — come from?”

“Why should I tell you?”

“I’m prepared to bargain,” B said. “I’ll bud you off, and give you your own existence, and put you on an Earth capable of sustaining your life, but one that hasn’t developed any sentient species. You’ll get to live in a natural paradise, which is better than you deserve.”

“A planet teeming with things I can kill? Interesting.” The Host showed his teeth again. This time, he licked them, and the points of his teeth drew blood from his tongue.

#

Hours later — not that time mattered here, but subjectively, it had been a long day — B sat at the table in the gazebo staring down into a cup of espresso. “The cloak comes from another universe. From Outside. Which, I mean — I figured. But what I didn’t know is, the reason it’s here.”

“Vanguard of an invasion force?” Henry sat with his arms crossed over his chest, frowning. Despite how distracted he was, a good 40% of the collective admired the way Henry’s crossed arms made his biceps bulge.

B shook his head. “No. The cloak was a criminal in its own reality. ‘Criminal’ isn’t exactly the right word, apparently — they don’t make a distinction between natural laws and laws created by sentient beings there, but apparently it’s also possible to break natural laws there, don’t ask me how. The cloak — the thing we call the cloak — did that. Violated something fundamental. And its punishment was being sent to our universe. Banishment. Exile.”

Henry frowned. “Wait. So we’re like… Australia? And the cloak is a British convict? Our multiverse is a penal colony?”

“More or less. With just a single prisoner. Except, of course, this being a multiverse, that prisoner has multiplied, in a way.”

“So… why am I dreaming about it?”

B winced. “This part, I figured out for myself. I fucked up, Henry. I had two cloaks together in one reality, and I took them both to a third reality, one with an uninhabited Earth, making my own attempt at banishing them. The cloaks are Outsiders, so it doesn’t exactly break my rules to put two of them in one reality, even though usually duplicates inhabiting the same reality is a no-no, one of the things I’m meant to guard against. The cloaks are… sort of outside my jurisdiction, so it’s okay. But I think passing through the membranes between realities so many times taught them something. The cloaks have senses I can’t even imagine — and since I’m capable of simultaneously watching everything throughout the past and into possible futures in every reality, those are some badass senses.” He ran a hand through his hair. “The cloaks must have figured out something about reaching through the membranes, even in their dormant state, when they’re just capable of whispering. So they’re whispering to you, Henry. They know they can’t overcome me — I’m billions of powerful psychics rolled into one — but you’re a singular creature, and a potential host.”

Henry whistled. “They’re trying to seduce me? They should work on their technique, because nightmares of utter destruction and choking to death in the gutter and ODing on needles full of junk aren’t really tempting me — ”

Not far away, just down the path, the front door of the house opened. That shouldn’t have been possible, because there was nothing else conscious and alive in this place to open a door.

Another Henry stepped out of the door. Except this Henry was wearing something that looked, at first glance, like a purple cloak, lined inside with white. To Bradley’s more advanced eyes, the cloak was revealed as something else: shaped a bit like a manta ray, but covered in eyes, and fringed all over with long, tentacular pseudopods, many ending in hooks and barbs, which wrapped around that other Henry’s body, and sank into his flesh. He came down the steps, and was followed by a second Henry, wearing another cloak — and finally by the Host, somehow freed from his prison in the basement, cloakless, and gazing at the new Henries with naked lust and hate. Other exiled Bradleys followed — the cyborg, the fascist, the madman with the tentacle, and more.

“Bastard,” the Henry in front shouted. “You saved one of us, but not all of us, so many of us are dead, you could have saved us all, but you let us die!”

“Fuck,” Bradley said, and grabbed his Henry’s hand, and fled.

#

Henry was barefoot, wearing shorts and a t-shirt, but Bradley made sure he wasn’t cold, even though they were standing in frozen tundra. Standing in the place where the exiled cloaks should have been, and weren’t.

“They weren’t just whispering to you,” B murmured. “They were somehow whispering to all the versions of you, down the timestream, telling them I was a monster, that I could have saved their lives, and chose to let them die. Which…”

“You could’ve,” Henry said. “I guess. We’d have to put in a whole lot of extra bathrooms, though.”

B laughed, mirthlessly. “Yeah. I didn’t think it was practical — saving even one of you was an indulgence, and an abuse of power. Those visions of death in the gutter weren’t meant for you — they were meant for all the versions of you I didn’t save. And somehow, the cloaks opened doors, passageways, between realities. They shouldn’t be able to do that. They never could before.”

“When one monkey learns to use a stick to get ants out of an anthill, all the other monkeys who see him do it figure out how to imitate the trick,” Henry said. He shivered, despite the envelope of warmth B wove around him. “The cloaks saw you come and go here, checking up on them, and you said it yourself, their magics are way beyond what’s normally possible in our universe. They must have just learned to do what you do. So. What happens now?”

“Now?” B peered forward, into the most likely futures. “They breach the walls between universes,” he said. “Repeatedly. Using Henry — versions of you — as hosts. And once they find more versions of themselves in other realities, locked in boxes or hidden in closets or buried in concrete pits, those new cloaks take over the versions of me they freed from the basement. That merry band continues to breach the walls between realities, looking for more versions of themselves, the cloaks intermingle, the cloaks breed…” He shuddered. “They don’t conquer the multiverse, of course. Our realities can’t sustain that kind of damage, all those holes being torn between them. I’m the only one who can move freely from one place to another without doing damage in the process — I have a special dispensation. In a few months, the structure of the multiverse will be shredded and pierced and as fragile as rotting lace, until… it all falls apart. After that, the things from In-Between can’t tell the difference between our realities and their dark domains, and they surge in, and eat everything alive. ‘Eat’ is the wrong verb, but it’s close enough in terms of effect. Then the cloaks start to use them, the things In-Between, as hosts, and after that… I can’t see what happens after that, because none of me is left in that scenario.”

“So we’re screwed.” Henry sat down on the ice. “Hell, B. I knew you had a lot of responsibilities in your job, but…”

B frowned. “Wait. There’s a thread, a possibility, a vanishingly-small likelihood, a billion-to-one chance…” He whistled. “Billion-to-one. When you’re me, those are actually pretty decent odds.”

“What’s the play?” Henry said.

“We break the rules,” B said. “We go Outside. I can’t see what happens if we do that — it’s like asking a dog to see colors, or a man to see into the infrared, it’s beyond the limit of my senses — but there are futures where I try it, and I don’t see doom in those. I don’t see anything in them. They’re singularities, no information escapes from them. But when your choices are certain death or the great unknown, the only sensible choice is to go with the unknown.”

B squinted at the ice, and scuffed a line on the ground with the heel of his boot. He dragged his foot along, making another line, and a third, and finally a fourth, forming a rectangle about the size of a door. Then he lifted his foot and stomped down, hard, in the middle, causing the ice to crumble into a twinkling darkness.

“Down the hatch,” he said, taking Henry’s hand. His boyfriend didn’t hesitate: they jumped in, feet first, together.

#

After a dizzying interval of falling, B found himself sitting in a white chair, shaped like an egg, mounted on a pedestal. It was like something from a 1970s vision of the future. He swiveled in the chair, looking around. He was in a small white room, utterly blank, except for a circular red lens mounted in the center of one wall. Henry was nowhere to be seen.

“Where is my — ”

“He is safe,” a booming mechanical voice said, speaking from all directions at once. “Frozen in a moment of falling. Where he lands… that depends on the outcome of this conversation.”

B stared at the glowing red camera eye. “You’re one of the powers. One of the things… like me.”

“I am to you as you are to ordinary gods, and as ordinary gods are to mortals,” the voice said. “You may call me — ”

“HAL-9000?” B said.

“I appear in a form dependent largely on your memory and perceptions,” it said. “Even given your extra-human senses, you do not possess the sensory apparatus necessary to look upon my true form. I gather I appear to you as some sort of… killer robot?”

“Close enough,” B said. “So. Are you God? Not a god, but — the big one? The one at the top? The maker of the makers?”

“Hmm. No. No more than a gardener is God. The plants would grow regardless. The gardener merely encourages some growths, and discourages others, and occasionally resorts to weeding. Or pesticides. Or, in extreme cases, fire and salt. That is my relationship to the great complex of universes. All those universes exist, in their vast numbers, and I do what I can to keep them growing and healthy. And I try to make sure one doesn’t strangle another, or kill its neighbors by stealing all the sunlight. You may think of me as the Gardener, if you like. Such metaphors are limited, but they have their uses.”

“So the way I oversee the multiverse,” B said, “You do that for all the universes?”

“Essentially, yes. You have become a great disappointment to me, Bradley Bowman. You should not have stepped Outside. You have left your territory unprotected. Why?”

“I have a little problem,” B said. “With these cloaks.”

“Those motherfucking cloaks again?” the Gardener said, the profanity shocking B so much it made him flinch backward. “What have they done this time?”

B explained: about putting two of the cloaks in exile on a frozen planet, about Henry’s dreams, about the attack on his home, and about the likely futures he saw if the cloaks weren’t stopped. “Since these monsters came from Outside,” B said, “I couldn’t see any choice but to go Outside myself.”

“I will arrange a meeting,” the Gardener said. “A sit-down. Wait.”

So B waited. He wasn’t sure how long. He didn’t think it was centuries, quite. And he suspected the passage of time in this place — or non-place — had no bearing at all on the passage of time elsewhere. In any elsewhere.

The chair spun around of its own accord. Now there was a door on the wall opposite the Gardener’s red lens. The door slid open, and a tall, thin man walked through, ducking to avoid hitting his head on the jamb. He was dressed in a strange ragtag assortment of clothes — a plaid flannel shirt, a pink Easter bonnet, cutoff denim shorts revealing knees that appeared to be put on backwards, steel sabatons. His face was one only Picasso could have loved.

“Ambassador,” the Gardener said. “Meet the Guardian.”

So that’s what they call me, B thought. I’d wondered.

The Ambassador opened his mouth and spoke, but he didn’t move his lips, or tongue: words just emerged from the gaping mouth, as if from a concealed speaker. “We exiled the — ” a strange clicking noise, then the word “cloak” in a distinctly different voice — “to your universe. We did not realize that place was inhabited. By our standards, it scarcely is — vast empty spaces abound there.”

“True,” B said. “But the cloak has a way of making itself heard, and it found sentient hosts.”

“More than one host?” the Ambassador said, mouth gaping, eyes glazed over.

“Sure,” B said. “Lots of hosts, really. Maybe not billions, but probably millions — ”

“A moment,” the Gardener said, and the room filled with a harsh squealing sound, strangely digital. B understood, without knowing how he understood, that the Gardener was communicating with the Ambassador at a very high informational density and rate of speed.

“This creature oversees a multiverse?” the Ambassador said, its tone incredulous, even as its eyes remained blank. “A complex of branching realities, where every possible quantum outcome actually comes to pass? But — what an absurd way to run a universe! Where does the energy come from? If we’d realized, we never would have sent the — ” click, buzz, “cloak” — “there.”

B shrugged. “It’s just the way we do things back home. The problem is, the cloaks have learned to breach the realities, and they’re joining forces, massing, becoming an army — ”

“We understand,” the Ambassador said. “We… will help correct this. If the Gardener will permit it.”

“I’m open to suggestions,” the machine that wasn’t a machine said.

After much discussion — which happened in mere seconds, and not always audibly — they settled on a plan. “I’ll open the door,” Bradley said when they were done.

“And I will seal it,” the Ambassador said.

“Good,” the Gardener said. “Come back when it’s done, and I’ll let you know if it actually worked.”

#

B left Henry on the same paradise planet where he’d promised to strand the Host, because that world’s lack of sentient life made it less tempting for the cloaks to invade. Then he went back home, to his house outside reality.

The cloaks had made his beautiful chateau into their base. His gazebo was gone, razed flat, and the house itself had been bizarrely fortified, with a mishmash of medieval battlements and high-tech armor and weaponry. As if anyone would attack them here! The cloak was so dramatic.

He saw the scarred, fascist version of himself, pacing the battlements, but it didn’t notice him. B was pretty good at not being noticed. He wished he’d had that ability back in his mortal life, when he’d been an actor, and entirely too famous for comfort, at least for a while.

B strolled through the remains of the garden, sighing when he saw that all the plants — the most beautiful from all the realities under his care — were trampled flat. At a particular spot he bent down and dug in the soft mud with a spade, until he uncovered a hatch, perhaps four feet across, made of dull gray metal. A circular handle stood in the middle, and B grunted as he turned it, pushing with all his strength, eventually budding off a couple of instantiations of himself to help turn it and add their leverage.

Someone at the house began shouting, and bullets hit the ground all around him and his copies. A few bullets would have struck them, but he just shifted the bullets into timelines where they didn’t touch him instead, so no harm done. B and his buds hauled open the hatch door, and stood back.

There was a peculiar roaring noise, like a waterfall in reverse, and the cloaked fascist fell from the battlements and was dragged along the ground, feet first, toward the hole B had opened. He clawed at the dirt, grasping for purchase, fingers making long furrows in the mud. The cloak was torn from his shoulders by the terrific vacuum — a vacuum that didn’t affect anything else but the cloak. It went flapping past B, its countless red eyes rolling wildly, and then disappeared into the hole.

B waved his hands, opening conduits to the other realities where the cloaks existed. Pinpricks opened in the air around him, widening to the size of hula hoops, each a window into another world. After a few moments, flapping purple and white monsters began flooding in through the holes, some few dragging their hosts with them partway, most coming unattached. The cloaks poured into the hatch he’d opened, streaming in their untold numbers for what would have been a day and a night in a normal place, before the last one passed through, and vanished into the dark.

B closed his eyes and felt for anything wrong — the splinter, the chip of stone, the bit of shrapnel in the body of his multiverse — and found nothing.

He hauled the hatch closed, and spun the handle shut, and re-absorbed his buds. Then he collapsed, and slept in the mud for some time, even though he was meant to be beyond sleep.

#

“Where are they now?” Henry said. “The cloaks?” They were snuggled up together on the futon, looking up at the stained-glass skylights in the living room. All the other versions of Henry had been put back in their rightful places, and they all probably still hated B, but at least he had this one to hold.

“The farther you get from the center — which is the wrong word, but the right concept — the older the universes get,” B said. “Out on the very edge there are entirely dead universes, ones where heat death happened long ago, where it’s nothing but empty absolute zero. Universes where there’s only expansion, no big crunch, no cycle of creation, just ending and emptiness. The Gardener said we could send the cloaks there, and by combining my powers with those of the Ambassador, we opened a door, and created a sort of… magnet, or vacuum, or irresistible force… that drew things from Outside.”

“So are the cloaks dead?”

“Maybe? I don’t know if they can live in a universe without energy. But there are millions of them now, so maybe they can feed on each other? I don’t even know if they do feed. Maybe they’re breeding merrily, filling up all the available space with copies of themselves. But they’re walled off, is the main thing, in an entirely different universe.”

“They figured out how to pass between realities here,” Henry pointed out.

“Yeah, but that’s different,” B said. “The parallel realities I oversee are all in the same multiverse. This place where we sent the cloaks, it’s way out there, it’s Outside. Traveling between realities in the multiverse is easy compared to traveling between universes. It’s like the difference between walking from one room in your house to another and walking from your front door to another galaxy.”

“I hope you’re right,” Henry said. “But the cloaks can get into dreams, Bradley. How do you lock up something that can find you in your dreams?”

#

After making sure Henry was settled in at home, and that his own more dangerous alternate selves were recovered and sealed in their bell jars again, and that the holes torn in reality had been stitched up to the best of his ability, B finally returned to the Gardener’s chamber, where the Ambassador was waiting.

“Containment seems to be working, so far,” the Gardener said. “The cloaks are writhing and wriggling and testing the boundaries, but the universe where they’re trapped doesn’t give them much to work with. We seem to have averted disaster. For now.”

“I guess that’ll have to do, then.” B shook hands with the Ambassador, who only had four fingers, like a cartoon character. “Next time, could you not send your criminally insane monsters to my universe?”

“Of course,” the Ambassador said. “It was a regrettable error, and will not be repeated.”

“I appreciate you, ah, taking on a shape that’s familiar to me,” B said, since he assumed that was the point of the Ambassador’s horrible human costume. “But I was wondering. Are you all… like the cloak… in your universe? Your true form, I mean — with the eyes, the barbs, the tentacles…”

“Ah,” the Ambassador said. “You think the — ” click, hiss, “cloak” — “is native to our universe. It is not. It invaded us, or was sent to us, long ago, and caused great destruction before we banished it. Frankly, we do not know what it is, or where it comes from.” The Ambassador turned its head stiffly and looked at the Gardener’s glowing red eye. B looked, too. They waited.

“Don’t ask me where the cloak comes from,” the Gardener said at last. “Or what it is. Really. You wouldn’t like the answer.”

“Is that because the answer would be ‘I have no fucking idea?'” B said.

After a long moment, the Gardener said, “No comment.”